Human capital matters: the challenges and opportunities in Spanish education

Despite the progress made in recent decades, Spain still trails the most advanced countries in terms of educational attainment. Action is required at all levels to improve Spain’s human capital. Prominent measures include reducing early school leaving, modernising universities and vocational training and raising financial literacy.

Human capital allows us to move up the professional ladder and improve our quality of life and standard of living. At aggregate level, countries with greater human capital tend to be richer and more productive. Human capital depends on education and training. The education system has evolved considerably in recent decades, but Spain still trails the most advanced countries. Where do we need to improve to boost Spain’s human capital? And how do we do this?

What is human capital and how does it affect economic growth?

Human capital refers to individuals’ skills, knowledge, training and expertise. Nobel Prize winner Gary Becker![]() defined investment in human capital as the “activities that influence future real income through the imbedding of resources in people”, including schooling and on-the-job training.

defined investment in human capital as the “activities that influence future real income through the imbedding of resources in people”, including schooling and on-the-job training.

Human capital is a determinant of the differences among countries’ levels of development and of the prosperity of their people and firms. At the microeconomic level, there is a positive correlation between educational attainment and lifetime income![]() , and also between firms’ productivity and employee skills

, and also between firms’ productivity and employee skills![]() . From a macroeconomic standpoint, a greater stock of human capital can boost GDP growth (Figure 1). Not only because of the direct impact of education on the generation

. From a macroeconomic standpoint, a greater stock of human capital can boost GDP growth (Figure 1). Not only because of the direct impact of education on the generation![]() and dissemination of new ideas

and dissemination of new ideas![]() , but also because it amplifies the impact of investment in physical and technological capital

, but also because it amplifies the impact of investment in physical and technological capital![]() .

.

For individuals, more human capital means better jobs, higher wages and greater productivity. For countries, it means more development and wealth

Figure 1

IMPACT OF HUMAN CAPITAL ON THE ECONOMY

Source: Banco de España.

The challenges facing Spanish education

According to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), 35.8% of adults in Spain had no more than lower secondary education in 2023, compared with an OECD average of 19.2%. This indicates that a sizeable proportion of Spanish adults have a relatively low level of education. In addition, the OECD Survey of Adults Skills 2023 reveals![]() that literacy, numeracy and adaptive problem-solving levels among Spanish adults are also below the OECD average.

that literacy, numeracy and adaptive problem-solving levels among Spanish adults are also below the OECD average.

These figures suggest that in Spain there is ample room for improvement in the level of education and the skills acquired by individuals at different stages of their training, both of which are aspects that determine a country’s human capital.

We recently analysed the main challenges in our Annual Report![]() . They are:

. They are:

- High early school leaving: Early school leaving

has decreased significantly in recent decades. However, Spain continues to have one of the highest rates of early school leavers in Europe: 13.7% of 18-24 year-olds in 2023, compared with 9.5% in the European Union overall.

has decreased significantly in recent decades. However, Spain continues to have one of the highest rates of early school leavers in Europe: 13.7% of 18-24 year-olds in 2023, compared with 9.5% in the European Union overall.

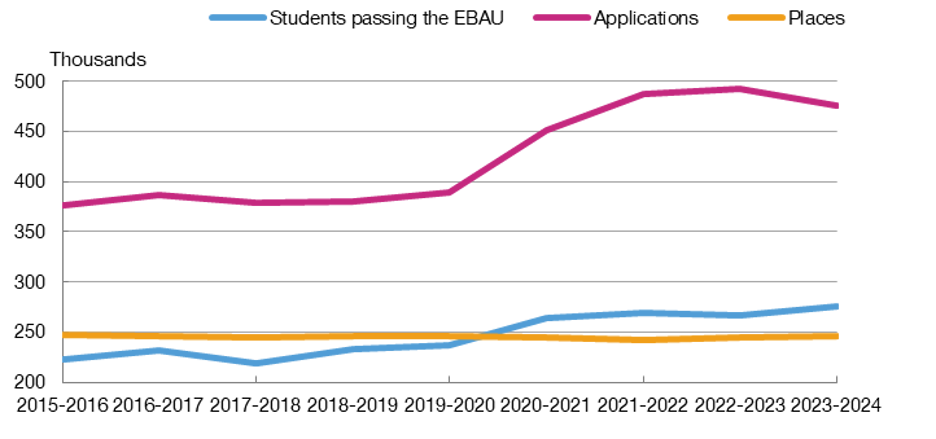

- Mismatch between public university education and market demand: Chart 1 shows that between 2015 and 2023 the number of people who passed the university entrance exam (EBAU

, by its Spanish abbreviation) rose by 24% and the number of applications to conventional public universities increased by 26%. However, in the same period, new places at conventional public universities fell slightly, by 0.3%. In addition, while there are more courses in the areas of study with greater job opportunities, the number of places available has not increased.

, by its Spanish abbreviation) rose by 24% and the number of applications to conventional public universities increased by 26%. However, in the same period, new places at conventional public universities fell slightly, by 0.3%. In addition, while there are more courses in the areas of study with greater job opportunities, the number of places available has not increased.

Chart 1

THE RISE IN STUDENTS PASSING THE EBAU AND IN APPLICATIONS HAS NOT LED TO AN INCREASE IN UNIVERSITY PLACES

SOURCE: Ministerio de Ciencia, Innovación y Universidades (UNIVbase).

NOTE: First-choice applications and places at conventional public universities.

- Roll-out of dual vocational training: The number of places offered in the dual system in the 2021-2022 academic year accounted for less than 5% of the total, despite the benefits of this type of training. For instance, the economic literature finds

that under the dual system in Spain, the number of days worked, income and job retention rates are all higher in the two years after graduation than under traditional vocational training programmes. However, at international level, the evidence is less conclusive as to whether the short-term returns from the dual model continue over the working life, particularly in a context of rapid technological change.

that under the dual system in Spain, the number of days worked, income and job retention rates are all higher in the two years after graduation than under traditional vocational training programmes. However, at international level, the evidence is less conclusive as to whether the short-term returns from the dual model continue over the working life, particularly in a context of rapid technological change.

- Improving financial literacy: As in other European countries, the level of financial literacy is low in Spain, as shown by the Banco de España’s Survey of Financial Competences 2021

. Specifically, only 65%, 41% and 52% of Spanish adults understand basic concepts related to inflation, compound interest and risk diversification, respectively.

. Specifically, only 65%, 41% and 52% of Spanish adults understand basic concepts related to inflation, compound interest and risk diversification, respectively.

Three main challenges require action: reducing early school leaving, easing the disconnect between university education/vocational training and market demand, and improving financial literacy

Possible measures

To reduce early school leaving, public policies should continue to encourage students to remain in the formal education system, especially considering that work experience is an imperfect substitute for formal education in the development of cognitive skills for workers with lower levels of educational attainment![]() . Various programmes, such as tutoring in small groups or with teachers from the same ethnic background

. Various programmes, such as tutoring in small groups or with teachers from the same ethnic background![]() , have proven useful in this respect. Furthermore, it would be advisable to provide students (and their families) with sufficient information on the employment returns to education, so that they can make informed decisions

, have proven useful in this respect. Furthermore, it would be advisable to provide students (and their families) with sufficient information on the employment returns to education, so that they can make informed decisions![]() about what to study.

about what to study.

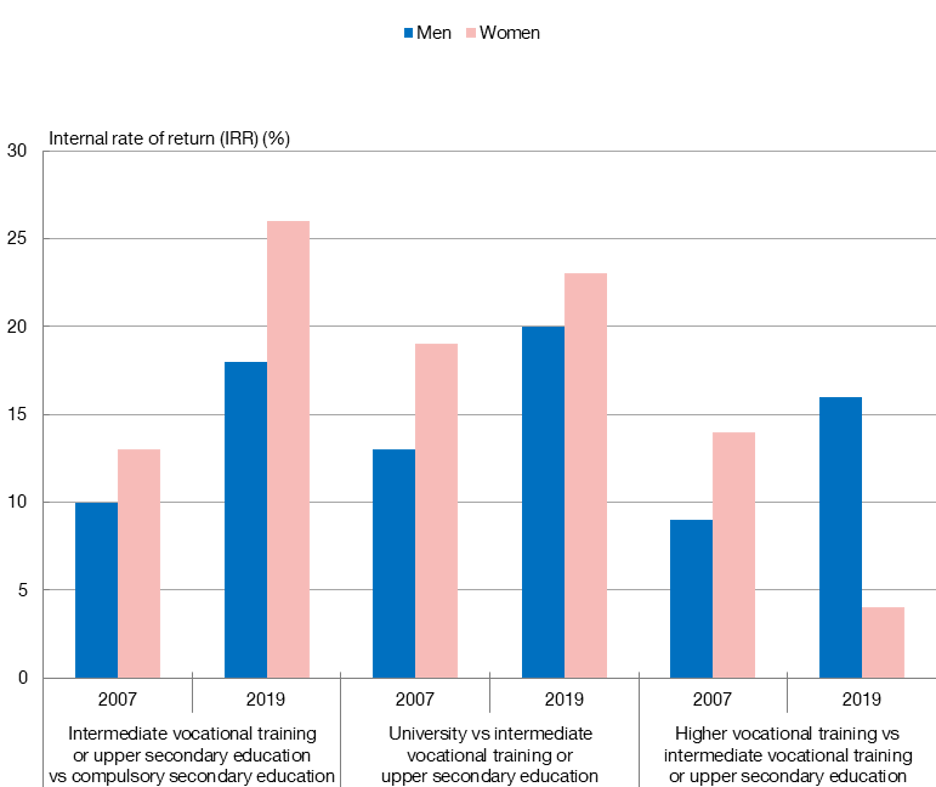

Chart 2 shows that in Spain the rate of return of remaining in education beyond compulsory secondary education is very high. In 2019 an upper secondary education or intermediate vocational training provided a return of 18% for men and 26% for women. Finishing university or higher vocational training provided an additional return of over 10% on average. Except for women completing higher vocational training, in all other cases this return was higher than in 2007.

Chart 2

IN SPAIN THE RETURNS TO EDUCATION ARE HIGH AND HAVE INCREASED

SOURCE: Banco de España, Spanish Survey of Household Finances 2008 and 2020![]() .

.

NOTES:

-The chart depicts the IRR to one level of educational attainment compared with another. The IRR to a level of educational attainment is defined as the discount rate that equates the sum of the present value of earnings over 50 years of work experience with the opportunity cost (the present value of income earned by not remaining in education).

-Gross labour income per year of work experience is obtained using a logarithmic regression of gross annual labour income restricted to a sample with the two educational attainment levels analysed, adding a dummy variable for the higher educational attainment level together with other variables. Drawing on the results of these regressions, labour income is estimated from 0 to 50 years of work experience and the IRR is calculated assuming that those with a lower level of education begin work two or four years earlier, depending on the level, than those with the next level of education. It is assumed that studying has no monetary costs.

-For further details, see Jansen and Lacuesta (2024) ![]() and Chart 2.3 of the Annual Report 2023

and Chart 2.3 of the Annual Report 2023![]()

In the case of university education, further action in addition to the new Organic Law on the University System![]() may be needed. Specifically, these measures should reduce the supply and demand mismatches in public university education, which have a bearing on equality of opportunity and the ability to undertake the green and digital transition. Further, the current university funding system should be assessed, focusing on aspects such as its sufficiency, equity and ability to foster excellence.

may be needed. Specifically, these measures should reduce the supply and demand mismatches in public university education, which have a bearing on equality of opportunity and the ability to undertake the green and digital transition. Further, the current university funding system should be assessed, focusing on aspects such as its sufficiency, equity and ability to foster excellence.

The Organic Law on Vocational Training![]() , approved in 2022, seeks to transform the vocational training system in Spain. To this end, it focuses on the dual system introduced in 2012 and on continuous training. To meet the ambitious targets set as regards the number of dual vocational training places, firms need the right incentives to generate these places. The continuous training system for workers established in the Law should also be subject to ongoing evaluation.

, approved in 2022, seeks to transform the vocational training system in Spain. To this end, it focuses on the dual system introduced in 2012 and on continuous training. To meet the ambitious targets set as regards the number of dual vocational training places, firms need the right incentives to generate these places. The continuous training system for workers established in the Law should also be subject to ongoing evaluation.

To raise financial literacy, the Financial Education Plan![]() , in which the Banco de España, the National Securities Market Commission and the Ministry of the Economy, Trade and Business participate, proposes a broad set of measures, which have already featured on this blog

, in which the Banco de España, the National Securities Market Commission and the Ministry of the Economy, Trade and Business participate, proposes a broad set of measures, which have already featured on this blog![]() , aimed at improving the population’s financial behaviour and habits. These measures should be flexible to adapt to the changing environment and their effectiveness should be assessed.

, aimed at improving the population’s financial behaviour and habits. These measures should be flexible to adapt to the changing environment and their effectiveness should be assessed.

To conclude, despite the headway made in recent decades, further measures are needed to continue to build up human capital in Spain. These improvements are particularly important at present, to drive the technological changes under way![]() and the green transition and to minimise the possible adverse effects that these transformations might have for certain individuals, jobs, firms and productive sectors.

and the green transition and to minimise the possible adverse effects that these transformations might have for certain individuals, jobs, firms and productive sectors.

DISCLAIMER: The views expressed in this blog post are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily coincide with those of the Banco de España or the Eurosystem.