The 2024 Nobel Prize: institutional quality boosts economic growth

The 2024 Nobel Prize in Economics has been awarded to Professors Acemoglu, Johnson and Robinson for their work on how the strength of institutions shapes the relative prosperity of nations. Their message is especially relevant today as institutional quality is declining worldwide.

14/10/2024

The 2024 Nobel Prize in Economics has been awarded to Daron Acemoglu![]() , Simon Johnson

, Simon Johnson![]() and James A. Robinson

and James A. Robinson![]() , for their work on how economic and political institutions develop and how they determine the prosperity of nations and the differences in prosperity between them

, for their work on how economic and political institutions develop and how they determine the prosperity of nations and the differences in prosperity between them![]() . Why is the quality of institutions central to economic development? How does Spain rank internationally? And how important is this work for central banks, and in particular for the Banco de España?

. Why is the quality of institutions central to economic development? How does Spain rank internationally? And how important is this work for central banks, and in particular for the Banco de España?

COMPOSITION 1

THIS YEAR'S NOBEL LAUREATES IN THE ECONOMIC SCIENCES

SOURCE: The Nobel Prize![]()

What contribution have the 2024 laureates made to economics?

There are rich nations and poor nations. Some poor countries manage to progress and develop. This is the case, for instance, of Spain and some Asian countries in recent decades. What are the root causes of these differences in countries’ wealth and why do they endure? Why do nations fail?![]()

The prize-winning economists believe the answer lies in institutional quality, as institutions determine the relationship between those in power (the ruling elites) and society as a whole. The higher the quality of a country’s institutions, the greater its prosperity and its possibilities for economic development.

Acemoglu, Johnson and Robinson draw a distinction between two types of institutions:

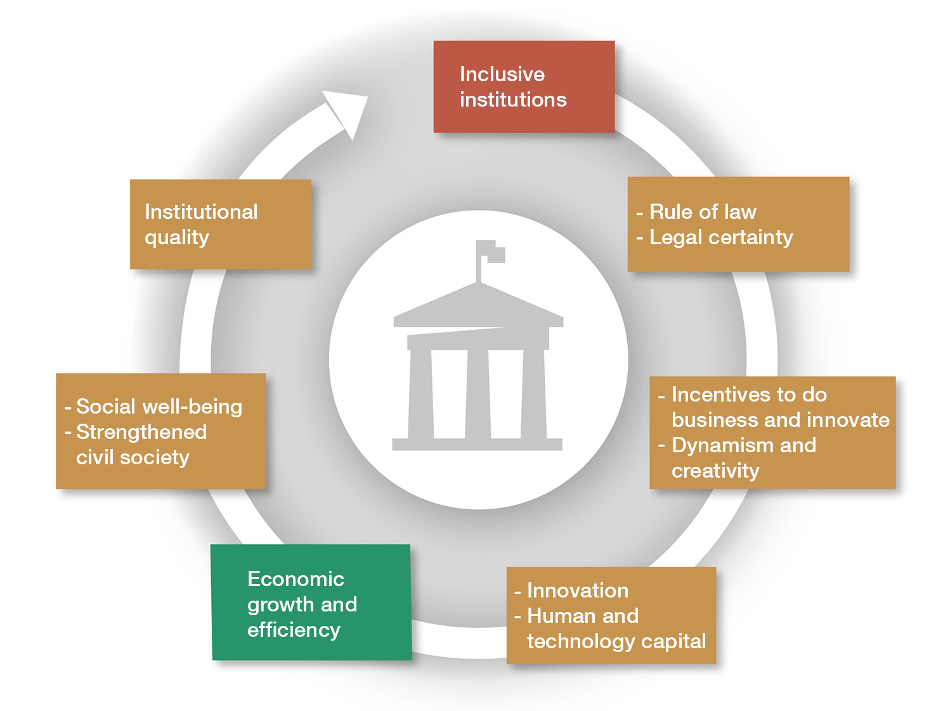

- Inclusive institutions, which are based on respect for the rule of law and are generally associated with democratic societies. In these institutions, the ruling elites allow citizens to function so that they are able to achieve their economic and social goals. Inclusive institutions thus incentivise behaviour that fosters the proper functioning of the economy, wealth creation and the development of civil society. In turn, a strong civil society demands better institutions, creating a virtuous circle of economic growth, social progress and continuous institutional improvement (Figure 1).

- Extractive institutions, where basic rights are violated and there is no legal certainty. Although such institutions are usually more common in autocracies, they can also be found in democracies. In this case, the ruling elites seek to extract resources from society for their own benefit. This reduces the incentive for societies to generate wealth, do business and innovate, and undermines social development.

Figure 1

INSTITUTIONAL QUALITY GENERATES A VIRTUOUS CIRCLE

SOURCE: Banco de España

Inclusive institutions facilitate wealth creation and the development of civil society, creating a virtuous circle of economic growth and institutional improvement

The Nobel laureates based their theory on an empirical investigation into European colonialism since the 16th century![]() ; specifically, on a comparative analysis of (more or less extractive) colonialism models and the outcomes in terms of economic development.

; specifically, on a comparative analysis of (more or less extractive) colonialism models and the outcomes in terms of economic development.

One of the key implications of their theory is that the inequality gap between nations is not easy to close. Institutional strength encourages not only economic growth but also further institutional improvement. Conversely, institutional weakness hinders not only development but also institutional strengthening, which in many cases makes it difficult to close the gap.

Another consequence is that, in order to be effective, reforms require the right context. The Nobel laureates specifically analysed this question in a paper on central bank independence![]() . In recent decades most central banks have become independent of governments. This independence is understood to be one of the reasons why inflation has fallen in many countries. The paper showed that countries with extractive institutions were less able to control inflation. Why was this? Because the demands of the ruling elites sustained a certain level of price distortions, which ultimately generated inflation.

. In recent decades most central banks have become independent of governments. This independence is understood to be one of the reasons why inflation has fallen in many countries. The paper showed that countries with extractive institutions were less able to control inflation. Why was this? Because the demands of the ruling elites sustained a certain level of price distortions, which ultimately generated inflation.

How to break the vicious circle between institutions and prosperity? Through changes in social equilibrium. One problem with extractive ruling elites is their lack of credibility and society’s mistrust of them. To hold on to power they feel the need to promise changes to improve the well-being of the population. But these are promises they rarely keep, which generates social unrest. This unrest can be silenced either with more repression, or with the ruling elites realising the need for reforms and for handing over some political power to society. In this latter case, change can occur gradually and peacefully, as in democratic transitions, whereas in the former, it can be sudden and convulsive, as in revolutions.

In their recent book Power and Progress![]() , Acemoglu and Johnson also analyse the role played by technology and innovation in driving economic growth and shaping power. They acknowledge the positive (democratising) impact of technological progress on institutions throughout history. However, they also warn that the present technological revolution, led by the internet and artificial intelligence and concentrated in large corporations, could have a negative impact on employment and the quality of democracy itself.

, Acemoglu and Johnson also analyse the role played by technology and innovation in driving economic growth and shaping power. They acknowledge the positive (democratising) impact of technological progress on institutions throughout history. However, they also warn that the present technological revolution, led by the internet and artificial intelligence and concentrated in large corporations, could have a negative impact on employment and the quality of democracy itself.

How has the quality of institutions evolved in Spain?

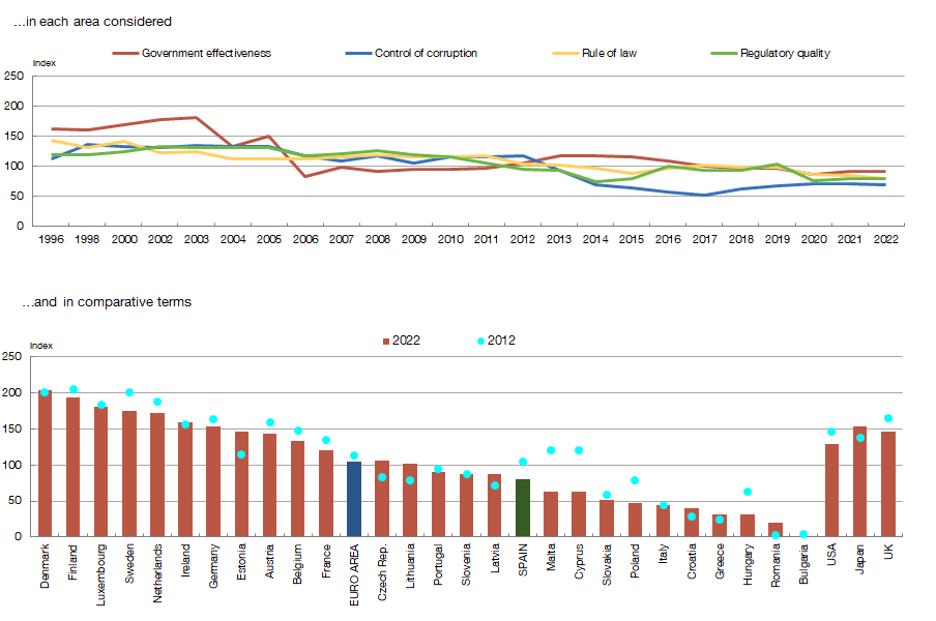

For the last 25 years the World Bank has been compiling Worldwide Governance Indicators![]() in which it assesses four main areas of institutional quality: control of corruption, government effectiveness, regulatory quality and the rule of law. This global analysis makes it possible to make cross-country comparisons. The Banco de España is also paying growing attention to these issues, through the research work of its economists

in which it assesses four main areas of institutional quality: control of corruption, government effectiveness, regulatory quality and the rule of law. This global analysis makes it possible to make cross-country comparisons. The Banco de España is also paying growing attention to these issues, through the research work of its economists![]() .

.

How does Spain rank in these classifications? Chart 1 shows that institutional quality has declined in all four areas since the mid-1990s. It also shows that, although institutional quality has decreased in most countries in recent years, the fall is sharper in Spain, which has moved down in the global ranking and is below the European average.

Chart 1

SPAIN’S INSTITUTIONAL QUALITY HAS DECLINED

SOURCE: Banco de España, Worldwide Governance Indicators![]() (World Bank), ECB

(World Bank), ECB![]() .

.

NOTES: Each of the institutional quality indices compiled by the World Bank include several dimensions on a scale of -250 (low quality) to 250 (high quality). A score of 250 indicates that a country is the best in a specific subcategory or for the aggregate index..

Institutional quality has declined across the globe in recent years, but in Spain the reversal has been greater

Institutional quality has been the focus of growing attention in recent decades, thanks to the contributions of the new laureates. However, some conclusions are inconsistent with recent developments. For instance, how can we reconcile this theory with the strong economic development experienced by various economies with undemocratic regimes, such as China? Or the recent institutional deterioration in developed democracies which goes against the idea of the virtuous circle? None of this weakens the main thesis of the Nobel prize-winners, which is that strong institutions boost growth. But it is a timely reminder in these uncertain times that all public institutions, ourselves included, must work to improve our quality.

DISCLAIMER: The views expressed in this blog post are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily coincide with those of the Banco de España or the Eurosystem.