Why do gender gaps still exist at work? The latest Economics Nobel laureate has the answer

The gender gap in the labour market closed considerably during the 19th and 20th centuries. However, this process of convergence, both in labour market participation and wages, has slowed in the last two decades. Claudia Goldin’s research is key to understanding why.

07/03/2024

Women’s entry to the labour market was one of the most important economic and social achievements of the last century, and one that arrived in Spain a little late. But gender gaps still exist in the labour market and, more concerningly, have stopped narrowing. In this post, we look at why the gap narrowed in the first place and what obstacles still lie ahead. We will do so with the help of Claudia Goldin![]() , the last winner of the Nobel Prize in Economics, an award that recognises the growing importance of gender studies in economics.

, the last winner of the Nobel Prize in Economics, an award that recognises the growing importance of gender studies in economics.

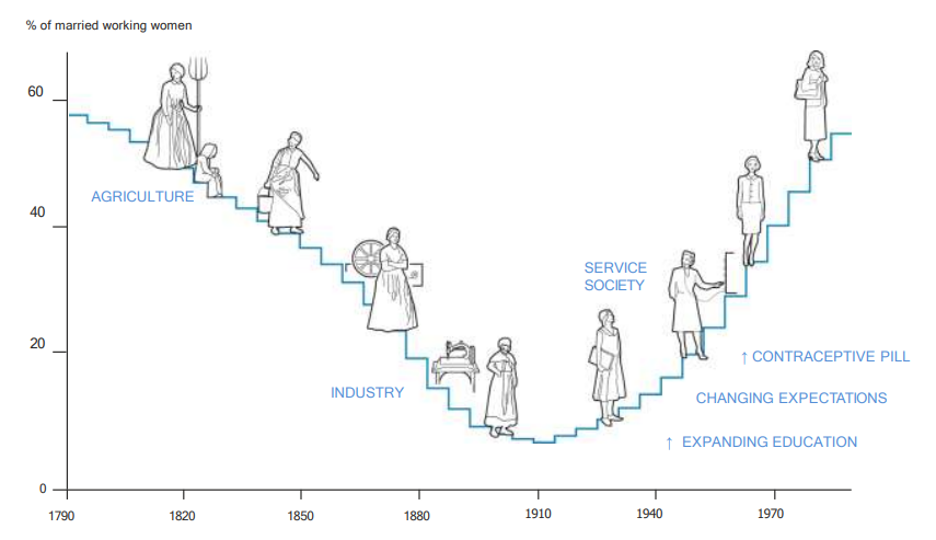

The function linking economic development and women’s participation in the labour market is U-shaped

In the 19th and 20th centuries, married women’s labour market participation did not grow linearly, in parallel with economic development, but rather traced a U-shaped function, as you can see in Chart 1.

Chart 1

WOMEN’S LABOUR MARKET PARTICIPATION IN CENTURIES PAST: A U-SHAPED FUNCTION

SOURCE: Goldin (1995)![]() , Jarnestad (2023).

, Jarnestad (2023).![]()

NOTE: Married women’s labour market participation in the United States, 1790-2000.

Why? The evidence![]() gathered by Claudia Goldin in the case of the United States reveals the following:

gathered by Claudia Goldin in the case of the United States reveals the following:

- When family incomes were extremely low and agricultural activities predominated, women participated massively in the labour force, at a rate of around 60%.

- With the shift towards a more industrialised economy, women’s labour market participation fell. As family incomes increased and were sufficient to maintain their standard of living, it was no longer necessary for women to have to work outside the home (income effect).

- Women subsequently rejoined the labour market owing to the emergence of administrative jobs and access to education (substitution effect).

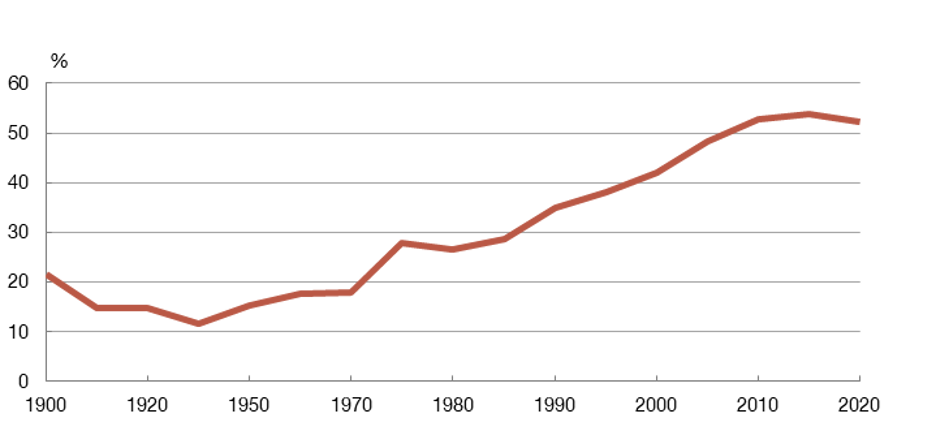

In the case of Spain, Chart 2 shows that the female participation rate up to 2010 was also U-shaped, although less markedly so, and it lagged somewhat behind the United States, since the industrialisation process in Spain took place later.

Chart 2

WOMEN’S LABOUR MARKET PARTICIPATION RATE IN SPAIN, 1900-2020

SOURCE: OECD. Stat, Long (1958)![]() , Heckman and Killingsworth (1986).

, Heckman and Killingsworth (1986).![]()

NOTE: Proportion of women aged 15 years or older that is economically active.

Recent developments in the gender gap. Why has it stopped narrowing?

To better understand the rising segment of the curve, we must look at both supply-side and demand-side effects, that is, women’s increased access to education and the proliferation of administrative jobs.

One of the arguments set out by the Harvard professor is that the introduction of the contraceptive pill in the late 1960s represented a decisive turning point in women’s expectations![]() . Oral contraceptives made it easier for women to plan their future – putting off marriage and the arrival of their first child. Being able to control when they had children encouraged them to invest in their education and career.

. Oral contraceptives made it easier for women to plan their future – putting off marriage and the arrival of their first child. Being able to control when they had children encouraged them to invest in their education and career.

In addition, the potential returns on education were greater for women than for men![]() , since studying opened doors to office jobs that paid more and had better working conditions than factory jobs.

, since studying opened doors to office jobs that paid more and had better working conditions than factory jobs.

All of the above, alongside technological advances in homes, made possible what Claudia Goldin called the “quiet revolution”![]() : a shift in women’s expectations and attitudes to their career that had an impact on economic growth comparable to that of globalisation itself.

: a shift in women’s expectations and attitudes to their career that had an impact on economic growth comparable to that of globalisation itself.

However, the recent Nobel laureate believes that the last chapter of the “grand gender convergence”![]() has yet to be written.

has yet to be written.

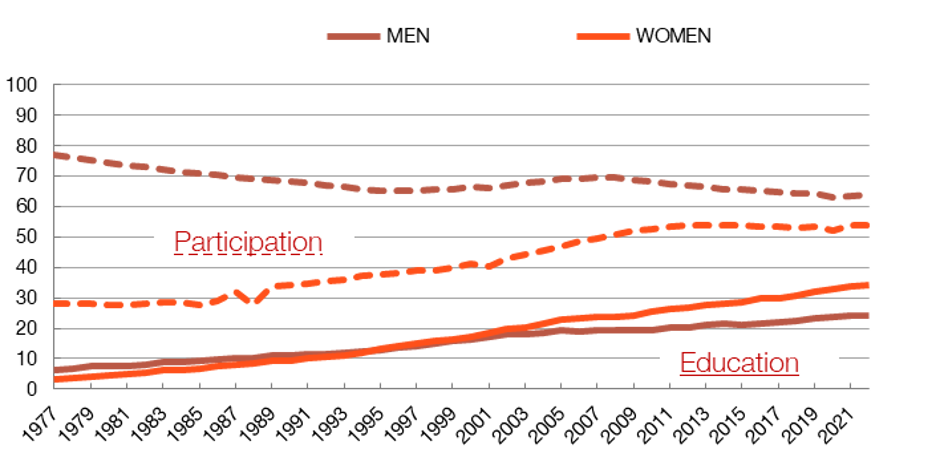

Despite the progress made, differences between men and women in the workplace still persist.The increase in women’s labour market participation has slowed, as Chart 3 shows for Spain.

Chart 3

SPANISH WOMEN HAVE OVERTAKEN MEN IN EDUCATIONAL ATTAINMENT, BUT CONVERGENCE OF LABOUR MARKET PARTICIPATION HAS STAGNATED

SOURCE: Labour Force Survey, INE.

NOTE: Population with tertiary education and labour market participation rate by gender in Spain, 1977-2022.

The same has happened with the gender pay gap. In the United States, the ratio of women’s median![]() annual earnings to men’s has barely changed over the last few years, after decades of improvement, particularly in the 1980s. In 1980, women aged 25 to 69 in full-time work earned 56% of what men earned. By 2000 that percentage had risen to 74%, but by 2010 it had barely budged, standing at just 77%.

annual earnings to men’s has barely changed over the last few years, after decades of improvement, particularly in the 1980s. In 1980, women aged 25 to 69 in full-time work earned 56% of what men earned. By 2000 that percentage had risen to 74%, but by 2010 it had barely budged, standing at just 77%.

Where are the biggest pay gaps between men and women? Goldin’s 2021 book Career and Family![]() showed that these differences widen after having children and are particularly large in those jobs that disproportionately reward being always available and working longer hours, for example, in sectors such as finance, business, law and academia. For the US economist, these “greedy jobs” tend to penalise interruptions more severely. These are also the jobs that have seen the biggest pay rises in recent years.

showed that these differences widen after having children and are particularly large in those jobs that disproportionately reward being always available and working longer hours, for example, in sectors such as finance, business, law and academia. For the US economist, these “greedy jobs” tend to penalise interruptions more severely. These are also the jobs that have seen the biggest pay rises in recent years.

The gap has not closed. According to Goldin, this is mainly due to motherhood, care responsibilities and higher pay for jobs that make it difficult to balance work and family life

In short, Professor Goldin’s research helps us understand why, despite the progress made, the gap between men and women in the labour market has not closed completely. According to Goldin, this is mainly due to motherhood, care responsibilities and the difference in remuneration between jobs that allow for work-life balance and greedy jobs.

DISCLAIMER: The views expressed in this blog post are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily coincide with those of the Banco de España or the Eurosystem.