Beyond GDP: how to measure economic welfare

GDP and per capita income are frequently used as synonyms of welfare. However, the concept of welfare is broader and more complex. As the economic and social developments of recent decades have made increasingly clear, economic welfare and well-being cannot be gauged by GDP alone. However, determining complementary welfare indicators and measuring them accurately is difficult.

11/12/2024

Analysts and the media are constantly discussing gross domestic product (GDP) and its growth. We all know that the higher the GDP, the better off we are. But how far does GDP reflect our true welfare? GDP is basically a measure of economic activity. As an indicator of welfare it is both limited and imprecise. In this post we explain the key differences between GDP, economic welfare and general well-being, and discuss alternative indicators for measuring the latter two concepts. We also look at how Spain measures up internationally depending on which indicator is used.

GDP measures the monetary value of the goods and services produced in a given territory. Alternatively, it can be defined as any of the following:

- the sum of consumption, investment and net exports (exports less imports);

- the total output of all businesses within a country;

- the sum of all incomes (wages, benefits, etc.) of economic agents.

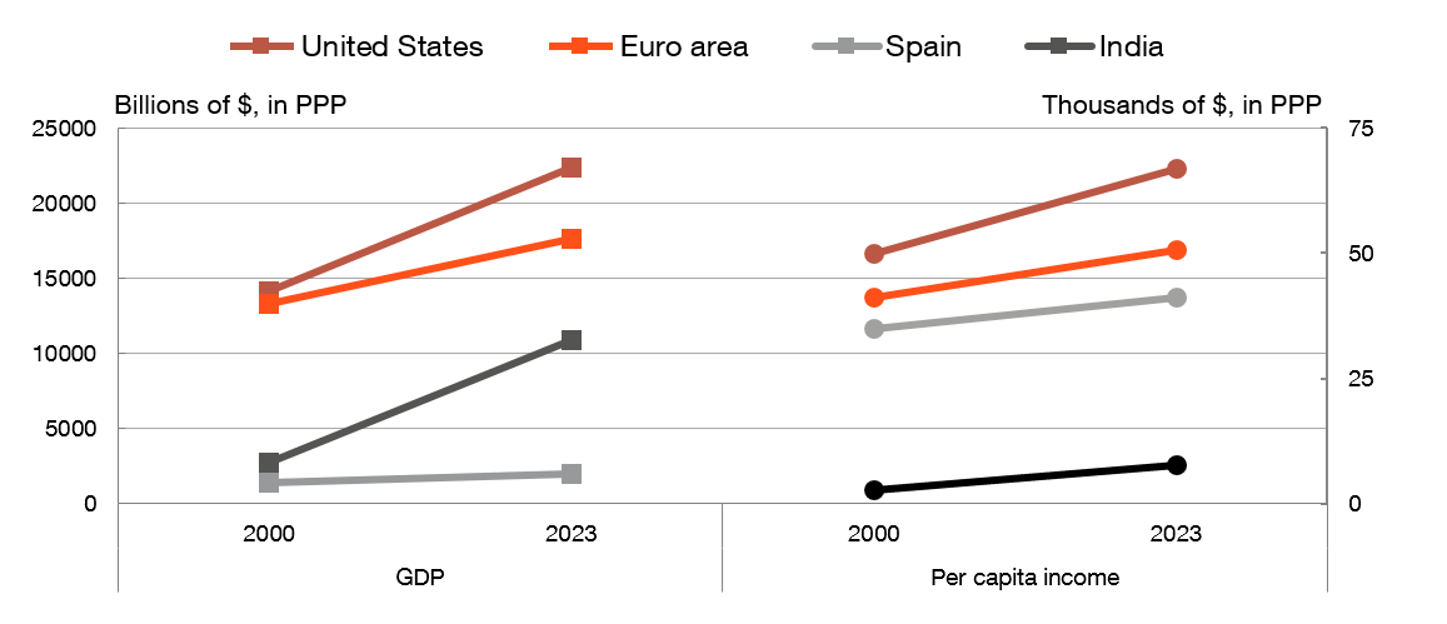

GDP and per capita income are widely used measures of a country’s economic development (see Chart 1). Based on these metrics, Spain ranks among the world’s 20 largest economies and is considered a high-income country![]() .

.

Chart 1

CHANGE IN GDP AND PER CAPITA INCOME IN SPAIN AND OTHER COUNTRIES. 2000-2023

SOURCE: IMF, World Economic Outlook, April 2024.

NOTE: Figures expressed in purchasing power parity (PPP) in dollars ($). The difference between the change in GDP and in per capita income owes to demographic developments. For regions with high population growth, such as India, the difference between the paths of each variable can be remarkable.

From GDP to measures of welfare

GDP has significant shortcomings as a measure of welfare, which is a far broader and more complex concept that encompasses all aspects shaping a society’s overall quality of life.

Welfare refers to quality of life, while GDP is an indicator of economic activity. When used to measure economic welfare, its shortcomings become apparent

We have known about these shortcomings for some time. Back in 1973, towards the end of the post-war economic boom, Nobel laureates William Nordhaus and James Tobin challenged the GDP-based definition and measurement of growth in their article Is Growth Obsolete?![]() In particular, they explored the sustainability of growth, especially when it entails the extraction of natural resources and environmental degradation.

In particular, they explored the sustainability of growth, especially when it entails the extraction of natural resources and environmental degradation.

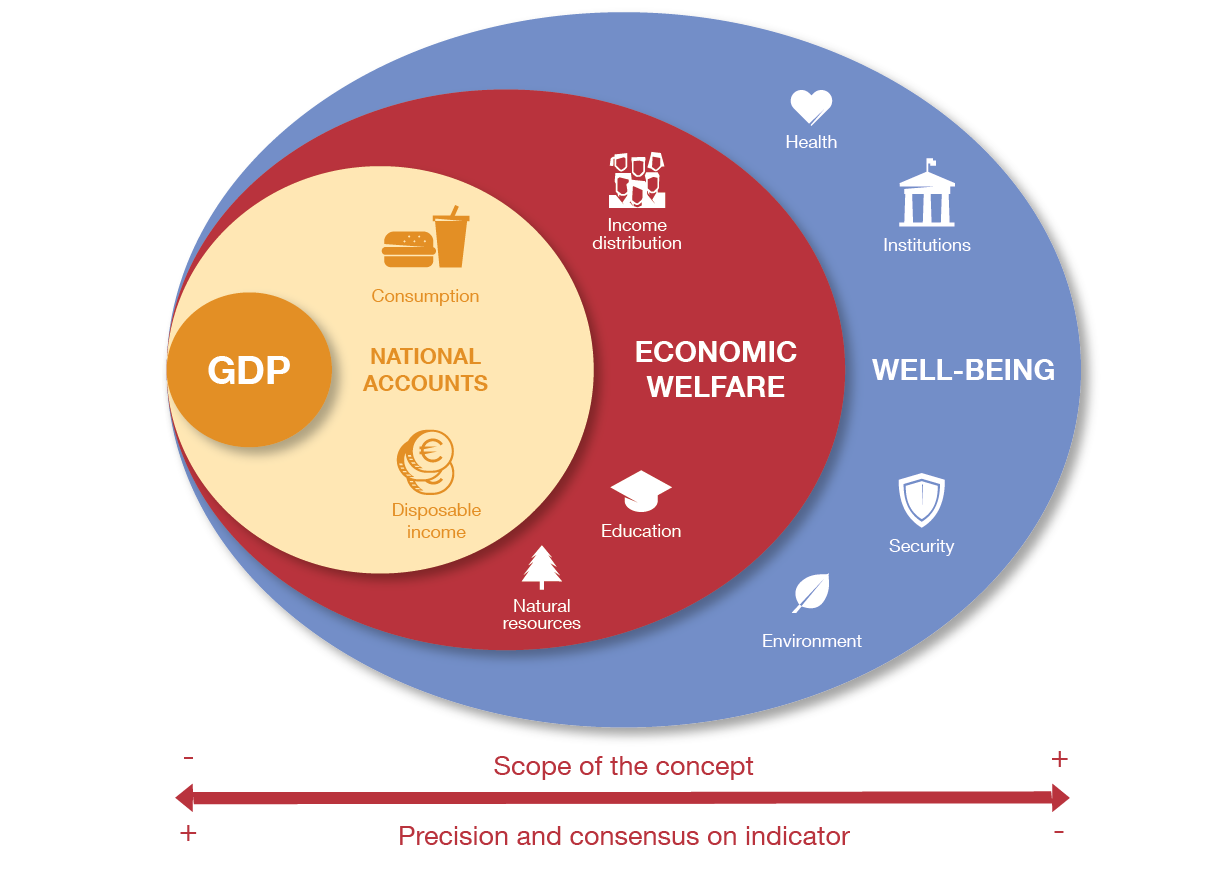

More than three decades later, in 2009, the Stiglitz Commission, led by another Nobel prize winner, published a report entitled Beyond GDP![]() . While the report did not criticise GDP itself, it did call for the development of alternative indicators to measure other aspects of welfare. As a result, more focus began to be directed towards existing but seldom-used indicators, and new indicators were developed that covered other crucial aspects of well-being (see Figure 1):

. While the report did not criticise GDP itself, it did call for the development of alternative indicators to measure other aspects of welfare. As a result, more focus began to be directed towards existing but seldom-used indicators, and new indicators were developed that covered other crucial aspects of well-being (see Figure 1):

- Economic welfare. Despite being an important concept, there is no universally accepted definition of economic welfare. It is typically measured using, in addition to GDP and various national accounts items (like consumption and disposable income), other concepts such as education and income distribution, which are not included in GDP but are unquestionably critical for a country’s economic welfare. For instance, when income inequality is high (which is often the case in developing countries or those with poor income redistribution), overall economic welfare tends to be lower.

-

Well-being is an even fuzzier concept than economic welfare and is even more open to debate, as it depends on social and cultural preferences. As shown in Figure 1, it often encompasses a long and wide-ranging list of additional factors, such as health, the environment, security and the quality of institutions -or governance-. Even happiness has been included in this mix.

Figure 1

FROM GDP TO WELFARE. SCOPE VS PRECISION AND CONSENSUS

SOURCE: Quirós and Reinsdorf (2020).![]()

NOTES:

-The concentric circles represent different perimeters and concepts of well-being. The items in each circle denote some of the indicators used to measure each concept.

-GDP is an indicator within national accounts. Economic welfare includes GDP, other national accounts items and other additional indicators. Further concepts are included to measure general well-being.

-The broader the concept, the less precise the indicators and the weaker the consensus on their measurement.

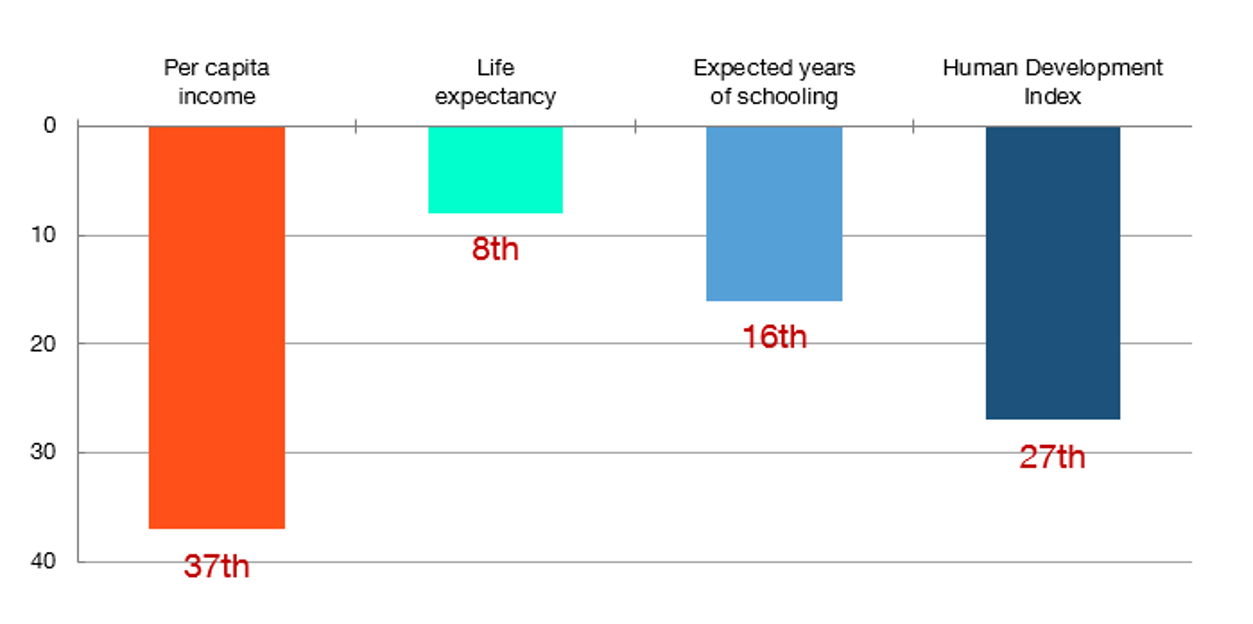

When these broader concepts are considered, Spain – like other European countries – climbs up the global ranking, as illustrated in Chart 2, which shows its position in the World Bank’s Human Development Index![]() . The index considers not only per capita income, but also health and education indicators. While this index is probably the most popular measure to gauge wellfare, it is still just one of many, with no consensus over the best approach.

. The index considers not only per capita income, but also health and education indicators. While this index is probably the most popular measure to gauge wellfare, it is still just one of many, with no consensus over the best approach.

Chart 2

SPAIN RANKS HIGHER IN TERMS OF WELL-BEING THAN IN TERMS OF PER CAPITA INCOME

SOURCE: Human Development Index (HDI), UN.

NOTES: The HDI aggregates various types of indicators in three areas: standard of living, education and health. Per capita income (or, more specifically, net national income) is the indicator for the standard of living; expected years of schooling are taken as the indicator for educational attainment; and life expectancy at birth is the indicator for health. The Human Development Index is the geometric average of the indicators used. The result is a ranking that should be interpreted with due caution.

The measurement and presentation challenge

The further we move beyond GDP, the more complex it becomes to define and quantify welfare. And no wonder: compared with the “objectivity” of GDP and market prices, how can we measure social welfare when there are so many different elements at play?

The further we move beyond GDP towards well-being, the more complex it becomes to define and quantify welfare, as it encompasses many diverse aspects that are difficult to measure

There is a critical matter in GDP measurement: the meaning of prices, which play a critical role. Prices often reflect the scarcity of some goods in relation to others, not necessarily their contribution to welfare. For example, although water is essential for life, it is much cheaper than diamonds, as the latter are very scarce, relatively speaking. Therefore, relative to the welfare they provide, water's contribution to GDP is tiny, while that of diamonds is very high (see Figure 2).

Figure 2

THE PRICES OF WATER AND DIAMONDS DO NOT REFLECT THEIR VALUE IN TERMS OF WELFARE

SOURCE: Reinsdorf y Quirós (2020)![]()

Furthermore, the growing digitalisation of the economy and society alike makes it more challenging to estimate macroeconomic indicators, particularly those linked to welfare. For instance, some digital platforms offer “free” services, such as videos, social media, communications and messaging. These transactions take place outside the market, and are free of charge or have no explicit prices; the cost is “merely” the surrender of personal data.

But, has your welfare and that of your household increased thanks to digital devices and social media? It certainly gives you food for thought. In any event, there is considerable consensus among economists that the overall effect of digitalisation![]() is that consumption, GDP and, above all, economic welfare and well-being tend to be underestimated and inflation is somewhat overestimated.

is that consumption, GDP and, above all, economic welfare and well-being tend to be underestimated and inflation is somewhat overestimated.

We also need to think about how to present these welfare measures. Should we use a composite indicator? Or a dashboard of complementary indicators?

The best-known composite indicator is the Human Development Index![]() (see Chart 2). Composite indicators neatly summarise all the available information into one number, but weights need to be assigned to each of their components, which always involves some subjectivity.

(see Chart 2). Composite indicators neatly summarise all the available information into one number, but weights need to be assigned to each of their components, which always involves some subjectivity.

Indicator dashboards don’t have this problem, since they present the information in its separate components. However, explaining these dashboards to the general public is difficult and a more in-depth knowledge of the subject is often required.

In sum, GDP is the most important measure of economic activity, but to effectively gauge social welfare it should be supplemented with other indicators. In any event, we must first clearly define what is meant by welfare and identify its various dimensions. However, despite the ongoing work on various fronts, we are still far from having a universally accepted way of measuring well-being.

DISCLAIMER: The views expressed in this blog post are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily coincide with those of the Banco de España or the Eurosystem.